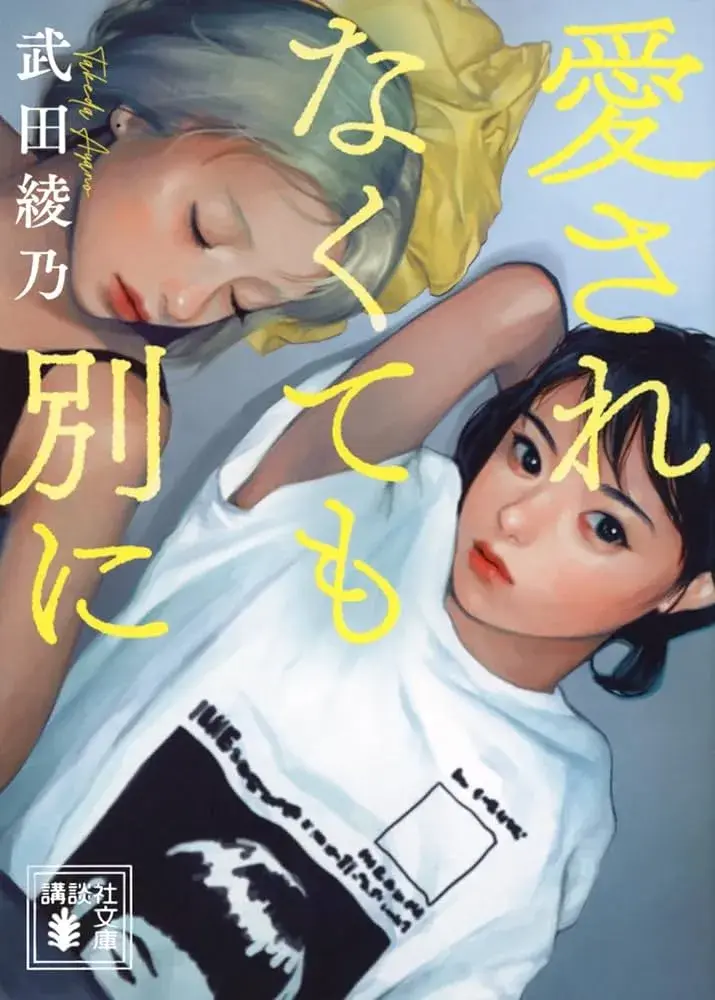

愛されなくても別に (Aisarenakutemo Betsuni)

8 1月 2024

The writer Takeda Ayano is known for her Hibike! Euphonium novels, a het bait series about high school students competing in brass band competitions. These books don't shy away from depicting stress and anxiety; relationships are fragile and it takes a lot of effort from the protagonists to maintain the status quo. If everyone can stick together and do their best, they may have a chance to win the trophy and bring glory to their schools. It's a grounded fantasy that will appeal to many readers of all ages, myself included.

However, when I followed her works, I found that the series limited her expression and talent. While the excellent Kyoto Animation anime adaptations made her a literary celebrity, it also meant that she had to churn out Euphonium novels forever. And when she writes other books, she's the Euphonium author trying something different.

As much as I like to think I'm objective, I know I'm part of the problem. Buying her Euphonium books out of an obligation to support her, rather than because I like the direction of the series, feels counterproductive. I stopped: I wanted to see Takeda write a book that wasn’t The Fluffy-Haired Adventures of Oumae Kumiko. I know Takeda can write something that isn’t a romantic vision of high school.

And well, let’s just say 愛されなくても別に (Aisarenakutemo Betsuni) went beyond that.

The first page is unlike anything I've ever read before. The first line is the date (April 25, 2019) and the current minimum wage for Tokyo: 985 yen. The next line: Japan’s average minimum wage is 874 yen, and Kagoshima’s is 761.

After these dry lines, the narrator notes that working the same job for the same hour results in very different incomes. Economic forces are obviously at work, but we talk about equality without even trying to hide the inequality.

Finally, the first page ends with the narrator realizing that talking about this with your peers in college isn't going to win you any friends; if anything, people might distance themselves from your bad vibes. But she corrects herself: she doesn’t have any friends to begin with, so it's impossible to lose friends.

I remember being shocked when I read that first page on the plane. It's so drenched in this self-deprecating dread that it intoxicated me. It’s like the novel opened my head in college and spilled my thoughts onto the page, only with better prose.

This is how we’re introduced to Miyata, a university student who spends her free time working part-time at a convenience store. She has no communication skills and that’s fine with her: going to parties and making friends is an unnecessary expense for a struggling student. University is just the first step to getting a full-time job for her. And while she has a scholarship loan she can count on, she doesn't want to deal with exorbitant interest rates. The less student debt, the better.

Miyata knows that her life is boring. The only way she can pass the time at work is by talking to Horiguchi, a co-worker and anti-feminist. He complains about how men do everything while women don't before claiming later in the book that same-sex and heterosexual relationships are “equal” and he won't change his behavior towards some imaginary and victimized minority. And he'll wink at Miyata and tell her that raising questions about her sexuality is not sexual harassment. These irritating conversations are the most exciting part of her life and taking it away would make working on the job much more miserable.

As Miyata deflects Horiguchi’s debatebro comments, the writing carefully observes and follows her routine: she restocks the counters, operates the cash register, and sweeps the floor. This introspective narration matches her tempo so well that I felt like I was going through the motions while reading the book and picturing her daily life. When her shift finally ended, I could smell the fresh air and hear the birds chirping, just as she had.

She returns to her home where she is immediately greeted by her mom who demands food. Miyata loves her mother, even if she finds it exhausting at times; ever since her mom’s divorce a long time ago, she has to take care of the household chores while her mom pursues the affections of younger men. This time, she’s dating someone who is into gacha games{^1] and she’s very happy to show Miyata that she just got an SSR[^2] card of a cute anime character. On the other hand, Miyata’s father has abandoned her and, according to her mother, has refused to pay his share of the childbearing expenses. Miyata can only sigh and take up the burden herself.

Miyata is willing to sacrifice so much because she loves her mom and her mom loves her. This isn’t simply filial piety; they really do find meaning in each other’s company. However, she finds their affections for each other suffocating. It was only through compromise that she was able to enter higher education, agreeing to attend an expensive private university near her home. She wants to be free, but she also doesn’t want to be ungrateful toward her mother’s own sacrifices.

Reading these parts made me think of the Miyatas I know in real life. Stuck between the Scylla of familial love and the Charybdis of their own personal ambitions, they don’t really have a choice but to withdraw. Better to work obscene amounts of time than to think and confront these issues because at least the situation hasn’t gotten worse. It's easy to fool myself into thinking that they are "brave" people, but they are trying their best to be good and ethical people — rug-pulling their parents will be judged harshly by our societal standards. Unless the “bad parenting” is transgressive enough it makes news headlines, there is no recourse for children to voice their complaints. They have to love their parents, neighbors, and everyone else. Otherwise, they’ll be perceived as inconsiderate assholes who bit the hand that fed them…

Nevertheless, Miyata realizes she’s not the only one with shitty families. While begging people for lecture notes, Miyata learns from a reluctant schoolmate that the other worker at the convenience store might be dangerous. Not only does Enaga stand out from the crowd with her damaged dyed hair, but her parent is a murderer. This intrigues Miyata’s own morbid curiosity: could there be someone else whose life is worse than hers?

She approaches Enaga during her work shift and as they begin to talk, Enaga casually brings up how her father fucked her when she was younger. Enaga's mother found out, and after she left her father, her mother forced her into sex work. Enaga laughs about the situation: her mother was furious when she found out she wanted to go to college and threatened to post revenge porn of her on the web.

This “laughing matter” horrifies Miyata (and I’m sure many readers), but this is the life that Enaga leads. The only reason she stopped working as a sex worker is because someone tried to strangle her and she decided to do something safer like working in a convenience store. Enaga isn’t ashamed of her past life; in fact, she wants to be transparent about it if Miyata is serious about getting to know her.

And so begins this strange relationship between two women connected by their ambivalent feelings towards their fucked up parents.

This premise was so compelling to me that I read the entire book in two days, quite a feat considering the subject matter. Each scene has so much stuff happening that there isn’t really a place to stop. I wanted to know how far the book was willing to go in depicting the lives of college students abandoned by their parents in late capitalist Japan.

Every digression the book takes paints a picture that becomes more and more chaotic the more detail are included. Mundane conversations can turn into grim reflections: someone jumps into the train tracks and dies; everyone is frustrated by the delays and curses their death because work is more important than mortality. Miyata remembers how she was molested in the train to school and “laughed” because she didn’t have any breasts to speak of and the molester clearly didn’t get what he wanted. Repression is constantly expressed through sensory overload, with smell and touch returning again and again to traumatize Miyata.

There were times I had to stop reading and do something else. This is a testament to Takeda’s writing: she knows how to lure readers into her world only to suffocate them. Miyata’s narration is so effective that I get as angry as she does when it turns out that her mother is doing more than just filling the house with mobile gift cards. The situations can be so upsetting that what Miyata leaves unsaid makes it hard to take in.

Take this line:

家族、家族、その単語を、何度も繰り返し咀嚼する。奥歯に張り付いにキャラメルみたいな、粘り気のある言葉。

She thinks about the word “family” as if it could be chewed and stuck to her teeth like caramel candy. Although the figurative language of sweets should be a positive thing, the rhythm matches the way the character thinks and it suggests that — like candy — it’s hard to get the word off. It’s a cynical turn of phrase that condenses Miyata’s exhaustion and fatigue without going overboard. In fact, it’s the restraint in Takeda’s prose that makes the atmosphere so oppressive in climactic situations.

I also found the narrative structure to be mostly effective once I realized what was going on. The three chapters, owing to their original serialized form, are more like linked short stories with the same characters. This gives each episode a chance to culminate into something powerful and moving: they slowly build up relevant elements before unleashing into angry yet concise arguments against love in society without worrying too much about the overall story being a cohesive whole. This fragmented nature allows Takeda to rehearse the same idea in three different ways, each time elaborating on unique aspects.

But this is a risk when one considers how many readers read novels assuming that everything builds to the final pages. The second chapter takes a very different direction — Miyata is invited into a Japanese new religious movement — and it basically breaks away from the narrative flow. Experienced editors would likely raise their eyebrows and ask Takeda to delete this irrelevant chapter. I know I was disappointed and confused by this shift; I started regretting saying this was going to be a favorite book of mine on social media. However, once we understand what Takeda wants to say about love, it turns out to be an important chapter, even if it's very out of place.

Love is real, and that’s why it sucks. It is not an abstract concept or virtue but a social relation that binds people together in community. Describing it this way may sound like a positive thing in the eyes of the Twitter left, but it's not: we must rely on the love between the units of societies and us individuals. This timeless relationship, which transcends logic and emotion, is a curse for young people today.

It's easy for us to argue that love in abusive families like Miyata's and Enaga's is wrong and distorted, but what the book is trying to say is that this love is actually par for the course. The love we want from our friends, families, and “loved” ones is no different from the love Miyata wants from her mother and vice versa. This recognition born out of the obligation of love is not recognition but coerced. We have to put our own money and time into maintaining this relationship, or else we will be perceived as not loving people.

And as the book correctly brings up, this is best seen in textbooks that praise the value of familial love without considering the hardships of single parent families and children abandoned by their parents. Not only is this untrue and harmful but people will always try to live up to these hypocritical standards and look extremely fake as a result. Miyata learns that her parents are, for lack of a better word, “good” people; even though they ruined her life, she still loves them because she has to participate in the charade that love has created for her.

And that’s what Miyata and Enaga resent: this duty to reciprocate, regardless of the context, because love is a mutual relationship. In the second chapter, the two characters watch how everyone in this cult is building communal love for each other. The person who invited them feels at home here because she believes that people love her and she loves them. However, these relationships only exist because they pay outrageous amounts of money for soul-cleansing tap water and their membership in this community. Eerily, this chapter also implies that these cult activities are no different than the money and time we spend on networking, which we explored in the previous chapter. The colleagues and friends we make along the way are not people who really care about you, just like the artificial relationships between these cult members.

There is no reason to maintain these relationships from the book's point of view. All they do is prolong the rigmarole and hurt all the actors in the play. The story likes to set up contrived J-drama scenes where Miyata and Enaga are supposed to reconcile with the people who wronged them. Why do they have to pretend to cry and hug the people who wronged them? The narration mocks this setup and even indulges in depicting their perplexity when the protagonists don’t follow the script.

What Miyata and Enaga want is to live life without being loved or needing to love. They don’t want to receive affections from families, girlfriends and boyfriends[^3], and certainly not from each other. What they want is a recognition of their personhood without the burden of love.

Somewhere in the book, a drunk Enaga attempts to seduce Miyata into fucking her. However, she is rebuffed. Enaga chuckles and says that’s why she likes her; Miyata sees Enaga as Enaga, not as an object to be loved. What they want from each other is ultimately an affirmation of each other. And that's what makes their relationship so special to me: they want to like each other without being forced to by circumstances not of their own making.

Still, I've read reviews suggesting that this is a kind of "love," just a more alternative kind. However, I disagree with this reading because not only does it misreads how the book conceives of love is but the two protagonists are also making sure that they are not romantically bonded with each other. At the end of the novel, the characters aren't even on a first-name basis. There is distance between the two that is respected throughout the novel. The book does have its gay moments[^4], but the mutuality they seek from each other is each other’s warmth, that there is another person like them, and that they’re not alone.

This is the kind of gay story I want to read: not love but a rejection of solipsism.

Works like Jude the Obscure have addressed the "natural forces" of marriage and the "beggarly question of parentage," while yuri manga like Bloom Into You have shown how restrictive romantic love can be, especially in a heteropatriarchal world. Step out of fiction and we find pamphlets like Abolish the Family by Sophie Lewis saying similar things too. But they have somehow not gone as far as Aisarenakutemo Betsuni: it wants to abolish love in favor of something better, more in line with how our younger generation wants to live.

The book shakes its head when we ignore social problems by thinking that everything will be fine in the name of love and peace. Instead, it wants us to think seriously about what we want from our peers. It delves into disturbing material about family, cults, and trauma — subjects that cannot be reconciled with love — to show that what we really want from each other is someone to say, “Hey, it’s fine.”

It’s a simple phrase that is devoid of love and even sympathy, but these three words can remind us we are still in the inferno of the living[^5] with other people.

It’s not every day that I agree with the marketing copy of a book, especially something as bombastic as “this book can save people”. For my part, I feel relieved that a book spoke about the things I’m always thinking about.

But what does it mean for someone like Takeda to “create something that will provide solace for people who can’t find [it] in mainstream media?”[^6] Is this solace even worth it?

As I wrote this article, I came to the conclusion that a work that can save us from despair is one that reminds us that everyone lives in despair without creating illusions and platitudes. Reading such a book made me think about the toxic myths in my own life. It’s counterintuitive to challenge something like love, but there’s much value in reassessing it.

And the solace comes from being able to discuss taboo subjects without fear of standing out. Takeda's book has already been published and read by many people. Even if there are people who don't like the message, they can't just dismiss it as nonsense; there are people who read it and applaud it.

I'm not sure if all books will ever be as provocative as Aisarenaku to achieve "practical value" for the reader, but I'd like to read more books like this. I enjoyed this book and will like to see it reach a wider audience as well. This book, and hopefully many others, should inspire greater public conversation.

As for me, I’ve gained a newfound appreciation for Takeda Ayano as a writer interested in capturing the anxieties of my generation. I’m looking forward to whatever she writes next.

[^1}: Just in case people who don’t follow Japanese media are reading this, these are freemium mobile games that use predatory mechanics to get people to cough up money. They can be compared to “lootbox games”.

[^2]: Super Super Rare, the highest form of rarity in these games and usually the only useful category in these kinds of games.

[^3]: I suspect the reason why Horiguchi is so prominent in the story is that Miyata envies him for coming to this conclusion. Even though he's a kind of MRA guy, he doesn't want love from his menhera (lit. mental health, a description of anyone who's highly sensitive and prone to emotional relapses) girlfriends but sex. Miyata's sex negativity means she'll never be like him, but it's pretty obvious that she finds it interesting that he gets sex partners without getting into relationships.

[^4]: Takeda claims she wrote her first yuri work for an anthology much later. However, the third chapter of this book includes an aquarium trip and vivid descriptions of hands, common features in yuri manga. I cannot tell if she’s pulling my leg right now.

[^5]: The ending of Italo Calvino’s Invisible Cities lives rent-free in my head: “The inferno of the living is not something that will be; if there is one, it is what is already here, the inferno where we live every day, that we form by being together. There are two ways to escape suffering it. The first is easy for many: accept the inferno and become such a part of it that you can no longer see it. The second is risky and demands constant vigilance and apprehension: seek and learn to recognize who and what, in the midst of inferno, are not inferno, then make them endure, give them space.”

[^6]: The phrasing comes from a translated interview with the creator of Caligula Effect. The original Japanese text can be found in Den Faminico.